Read the original article here

Everybody who is somebody is rolling into Miami for Super Bowl 54. But accompanying the glamorous parade of celebrities, CEOs, Hall of Fame athletes and National Football League VIPs is an underground stream of no-name girls and young women often branded with bar-code tattoos on their inner lower lip, dulled by a diet of drugs, painted with makeup to look older, bruised or burned in discreet spots and living in a state of terror.

Trapped “in the life” of the sex-trafficking business, they are an essential element of the Super Bowl revelry permeating South Florida in the buildup to Sunday’s big game at Hard Rock Stadium. Their pimps, described as modern-day slave masters by law enforcement authorities, aiming to make upwards of $1,000 per night per woman under their control, have converged here for the same reason they converge on any mega-event city inundated with 100,000 mostly male visitors: Supply and demand.

Traffickers have already set up at resorts in Miami Beach or no-tell motels on Southwest Eighth Street or extended-stay hotels near downtown. They’ve placed ads on sex-for-hire and adult entertainment websites and they’re trolling lobbies, pool decks, bars and Super Bowl parties to find johns ready to pay $100 cash for 30 minutes in a room with a person they may think of as a prostitute but who is more likely one of 40 million victims caught in the $150 billion sex and labor trafficking industry. It is second only to drug trafficking as the world’s largest criminal industry, according to the International Labour Organization and the nonprofit Polaris Project.

“The Super Bowl in a beautiful, partying place like Miami is a bonanza for traffickers,” said Theresa Flores, a trafficking survivor. “You lock four girls in a room, barely feed them, threaten them, beat them, force them to have sex with men who are charged inflated rates, knowing you are at very low risk of getting caught. You can sell a human being over and over again. Your Super Bowl experience could easily net $50,000 in profit.”

The two weeks leading up to the Super Bowl, when targeting sex buyers is as easy as shooting fish in a barrel, has become a rallying time for the anti-trafficking movement. Advocacy groups provide training on how to recognize trafficking activity to hotel, restaurant and ride-share workers and launch awareness campaigns for the public in conjunction with the NFL and its sponsors. It’s A Penalty is running its third Super Bowl campaign after starting at the 2014 men’s World Cup. Police raise the alarm and emphasize collaboration between agencies.

Before last year’s Super Bowl in Atlanta, police made 169 arrests related to human trafficking, and that number was up from 110 in Minneapolis in 2018. Calls to trafficking hotlines increased 23 percent before last year’s game and two dozen victims were rescued, including five in one day as a result of tips from hotels.

For the organizations fighting the crime of trafficking, the Super Bowl is prime time because of the connection between sports and the sale of sex. The night before the 1999 Super Bowl in Miami, Atlanta Falcons player Eugene Robinson was arrested on Biscayne Boulevard at Northeast 22nd Street for offering an undercover cop posing as a prostitute $40 for oral sex. His teammates told the New York Times they weren’t surprised; many of the players had been visiting downtown to buy sex all week. Former University of Miami player Warren Sapp was arrested for solicitation at a Phoenix hotel the morning after he covered the 2015 Super Bowl for the NFL Network. Police said he fought with two prostitutes over money.

New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft’s road to the 2019 Super Bowl included a 14-minute stop on the morning of the AFC Championship game at the $79 per hour Orchids of Asia Day Spa in Jupiter, police said. He was charged with solicitation as part of a widespread sex-trafficking sting of massage parlors, where trafficked workers typically paid their bosses $30 per day for food and lodging at the strip-mall spas (sometimes sleeping on the massage tables) and 70 percent of the payment for each massage they gave during 12-hour shifts. The charges are still pending.

Florida ranks third nationwide in human trafficking cases, and Miami-Dade County is the biggest trafficking hub in the state, according to a report by the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office, which estimates that the average sex trafficking victim may be forced to have sex 20 times a day, seven days a week. The crime of trafficking is different from prostitution in that, as defined by Florida law, the trafficker uses force, fraud or coercion.

“This is not a gentleman’s offense. This is not a don’t-ask, don’t-tell offense,” said Nick Oberheiden, a defense attorney who has handled trafficking cases. “This is ownership and assault of a human being.”

Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle created the Human Trafficking Center in 2012 and opened a five-story building to house it in 2018. Her office has filed 619 trafficking-related cases — 36 percent involving minors — and capitalized on major sporting events, conventions and tourist-drawing occasions to crack down on pimps. Officers also search for victims at schools, health clinics and on the street.

“These are difficult cases because the victims are usually kids who have been traumatized, raped, drugged and isolated for so long,” Fernandez Rundle said. “Over the last decade the laws have changed to recognize and attack this type of crime and the predators. If we don’t hit the demand side, this business will keep growing. We take a victim-centered approach. We don’t blame the victim.”

The Jeffrey Epstein case, in which the multimillionaire financier was charged with sex-trafficking underage girls he lured to his Palm Beach and Manhattan mansions 11 years after he received a lenient plea deal on a prostitution charge, also improved public understanding of how traffickers manipulate and entrap victims.

Volunteers fanned out this week to spread the word to the public, educate business owners and make contact with victims.

“These girls have been hiding in plain sight for a long time and we didn’t notice them,” said Ellyn Bogdanoff, a former Florida state senator and chair of the nonprofit End Human Trafficking Inc. “A lot of us look back and realize something was funky. We should have called the police.”

Anti-trafficking signs posted around Miami prior to the Super Bowl by the Miami-Dade Women’s Fund and law enforcement agencies alert visitors and victims to hotline information. MIAMI-DADE STATE ATTORNEY’S OFFICE

Flores runs the SOAP Project (Save Our Adolescents from Prostitution), an anti-trafficking organization with 19 chapters across the U.S. She organized 600 volunteers to deliver 60,000 bars of soap and missing children flyers to 480 Miami-area hotels and motels. The soaps are labeled with a red sticker that says: “Are you being forced to do anything you do not want to do? Have you been threatened if you try to leave? Text 305 FIXSTOP for help. 1-888-373-7888, National Human Trafficking Hotline.”

“We want to bust the myths. These aren’t bad kids or prostitutes working willingly,” Flores said. “They are coerced and brainwashed.”

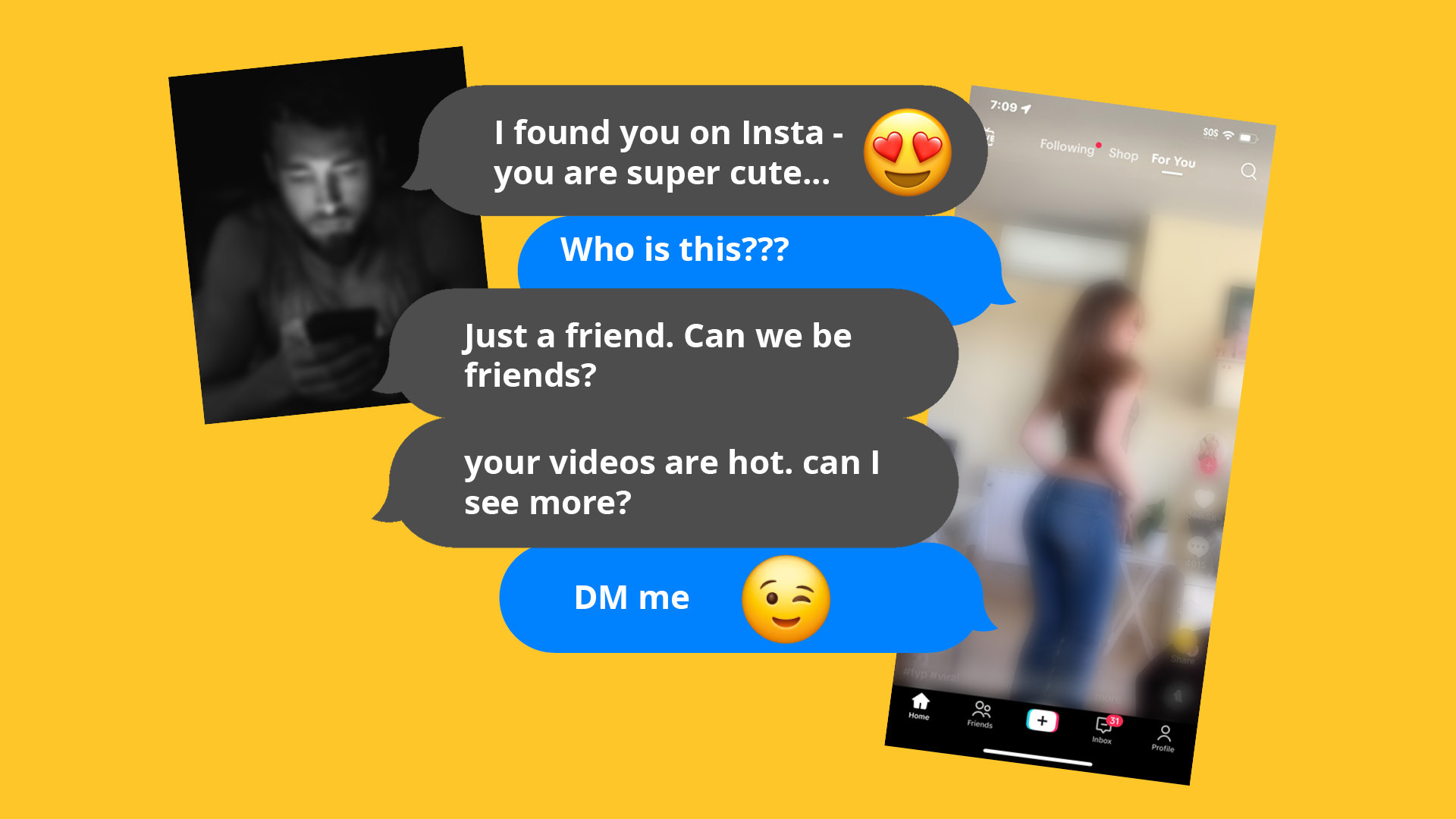

Traffickers recruit vulnerable people. They used to find girls at malls, bus stops or outside group homes. But now they spend hours mining social media to start chats and build trusting relationships with promises of love, security, money, opportunity, immigration documents. Once they have separated girls from their families, traffickers use threats of harm to the victims or their relatives, physical and sexual abuse, deception, debt bondage, drug addiction and manipulative tactics to force them into commercial sex.

“Traffickers are very smart and they can tell quickly, ‘I can get this one but not that one,’” Flores said. “They prey on troubled kids, insecure kids, foster kids, runaways. We’ve found about one third get trafficked by their own family; they were molested and sold by their own father. They feel guilt and shame. They’re scared to ask for help. They are told, ‘Nobody cares about you. This is the life. You are meant for it. You won’t find anything better than what you have with me.’”

Flores was 15 years old and living in upscale Birmingham, Michigan, a good student and track athlete at school when she was unknowingly groomed by an older classmate who pretended to be her boyfriend. One day he offered her a ride home, took her to his house instead and drugged and raped her. He took photos, and he and his cousins threatened to show them to her parents if she didn’t “work them off” by providing sex to men in hotel rooms.

“He knew where I lived, where I babysat. He threatened to kill my brothers. He killed my dog,” Flores said. “Inside you’re screaming but you’re too scared to tell anybody. You think, ‘I can earn those photos back soon and it will all be over.’ You don’t realize you’re a trafficking victim. You don’t know that word.”

Two years later, Flores’ father was transferred and she moved away, later finding out that the young men were affiliated with a Detroit-area mafia family.

“We want to reach a victim in her worst moment imprisoned in that hotel room,” said Flores, author of “The Slave Across the Street.” “And teach the owner or clerk to recognize a girl in trouble, or a trafficker using that room for customers.”

Joyce Dixson-Haskette was 25 when she shot and killed the man who was trafficking her for sex. She spent 17 years in prison.

“They made him the victim and me the cold-blooded murderer,” she said. “The perception of those roles in our society is changing slowly. I still don’t understand how a man can kiss his wife and daughter goodbye and tell them to stay safe, and then during his trip out of town, he buys a girl the same age as his daughter. To say no one is being hurt is simply not true. It’s not a choice.”

Dixson-Haskette said she was victimized by a man who claimed to love her and promised to take care of her, then threatened to kill her two children if she did not comply with his demands. She retaliated after he nearly killed her.

“One night I was the entertainment at a party where he stripped me naked, stood me on a bed and invited five guys to hit me with pool sticks and place wagers on how many licks I could take before I went down,” she said. “When I blacked out, he wrapped me in a sheet and dumped me at a loading dock where a maintenance man found me and took me to the hospital. I had ceased to be a person. I was a piece of property.”

Dixson-Haskette became the first woman to earn a degree from the University of Michigan while in prison. She’s now a clinical therapist in Royal Oak, Michigan, where she works with survivors.

Victims can be enticed into trafficking by a romantic partner, a father figure or a job scam. Jeffrey Cooper persuaded college students from Kazakhstan to come to Miami Beach to work at a yoga studio and helped them secure visas. But once they got here, Cooper ordered them to perform erotic massages and sex acts for money, according to 2011 court records. He advertised the women on Backpage.com, a classified ads website that was later abolished, offering “sensual body rubs” at a “lovely waterfront location.” Cooper was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

There are telling signs: Traffickers don’t look like a parent or guardian. They pay in cash. At hotels, they keep the Do Not Disturb sign on the door and men are constantly in and out of the room. The people they have in servitude may appear fearful, tense, submissive, malnourished, disoriented, or they have no form of identification, no cellphone and little luggage, said Alexandra Perron from the advocacy group A21.

“It’s all about control of their minds, bodies and souls,” Perron said. “He flatters her, builds a connection, tells her she can achieve her goals with him, pays for her classes, clothes, modeling photos, doctor appointments. He tricks her into the life: ‘You need to service these men because I’ve been helping you.’ He will beat another girl and warn ‘I’ll do this to you if you run.’ He might abuse an animal in front of her. He forces her to get a tattoo signifying she belongs to him or is part of his ring. He takes her on the road.

“My co-worker was trafficked back and forth across the country for seven years, on the circuit to big events, meeting sex buyers in high-end hotel lobbies and restaurants. These victims develop Stockholm Syndrome with their captors. They can’t escape.”

For all the attention that trafficking receives in Super Bowl cities, the arrest, prosecution and conviction of traffickers remains at a low level compared to the scope of the crime. One reason traffickers are able to stay a step ahead of the law is that the internet allows them to work in secret.

“Traffickers are getting more sophisticated. They’re using private chat rooms and private apps as well as dating sites,” said Esther Jacobo, director of Citrus Family Care Network and a former state prosecutor. “It’s a lot more undercover now. There are hundreds of different sites, and as quickly as one gets shut down another one pops up.”

For police, conducting a sweep of prostitution hot spots in Miami is easier than mounting a complicated investigation of traffickers and their organizations, which leave no paper trail of transactions. The lack of legal consequences for johns makes it difficult to pursue the demand side — although Florida did create a public database last year listing the names and photographs of individuals found guilty of soliciting prostitution.

But the greatest obstacle to catching traffickers is the typical reluctant victim, whose testimony is vital to making the case.

“Understandably, the girls won’t talk,” said Lissette Valdes-Valle, spokeswoman for the state attorney’s office. “They run away. They change their minds. They deny having a pimp and say, ‘No, he’s my boyfriend, he loves me.’ Maybe her idea of love is formed by the broken home she grew up in and this guy showed her kindness and she can’t turn on him. Or she’s an addict. Or she’s scared to death because he told her, ‘Shut up or I’ll get your little sister. She’s younger and can make more money than you.’”

But while Fernandez Rundle has touted her efforts to fight human trafficking, her office came in for harsh criticism for its dismissal of the credibility of four women and young girls who accused a Hialeah police sergeant of sexual assault. The prosecutors’ close-out memo cited the victims’ backgrounds as sex workers and runaways, saying they would make shaky witnesses in court. But women’s advocates say judgments like that only give license to traffickers.

The FBI stepped in, charging the officer in December.

Dr. Kimberly McGrath, director of programs and services at Citrus Family Care Network, said “one of the biggest advances” in the battle to curb trafficking is that law enforcement officers have learned how to approach victims more sensitively.

“Many minors don’t see themselves as victims of exploitation,” said McGrath, who runs the CHANCE treatment program for victims. “They see police as the enemy. They’ve been told that they will be put in jail, not their pimp.

“Recovery for these children is similar to that of domestic violence victims. It takes a lot of re-integration into society.”

Oberheiden, the lawyer, said the annual Super Bowl spotlight on human trafficking goes out as soon as the stadium lights are extinguished. He advocates tougher enforcement, improved coordination between overlapping agencies and incentives and protection for victims hesitant to cooperate.

“It seems to be a topic just once a year even though we know it’s a major organized crime 365 days a year,” he said. “Compared to healthcare and securities fraud, the conviction rate is tiny. We hear about drug trafficking constantly — the raids, the ringleaders, the sentences. Why don’t we hear about the criminals buying and selling people? Maybe it’s because the women come and go. They are replaceable, disposable, forgotten.”

(Do you need help? Have you seen something suspicious? Call 911 or the local trafficking hotline at 305-FIX-STOP or the national trafficking hotline at 888-373-7888 or text to BeFree, 233733.)